My Mum and Family

Members of the 2-19 Battalion marching down Castlereagh Street near the corner of Hunter Street in Sydney CBD during September 1940

The Grim Glory of the 2/19 Battalion A.I.F. Chapter 13 (written by Harold Burchell)

In accordance with the I.J.A. planning to send prisoners to Japan after the completion of the Thai- Burma railway, the first party was selected from various camps round the Kamburi area at the end of December, 1943 and in the main was an Australian party of 600. Only 15 of the 2/19 Battalion members were included, namely:

Sgt. Harold Burchell, Ptes. F. Asser, H. Badinier, E. Beasley, S. (Shorty) Cannon, Bernie Cantwell, Jim Collins, J. Cooper, C. Harvey, S. Herron, J. Holman, A. Jolly, R. McKean, J. Porter, H. Priddis, Mac Reid.,

The party was moved by rail mid January 1944 to Phnom Penh and then by river barge to Saigon. During the several months in Saigon, the group was employed on various tasks on wharves and godowns and municipal tasks in between the several abortive attempts to embark the prisoners for Japan, but owing to the presence of U.S.A. submarines in the area adjacent to the Philippines, the Japanese found great difficulty in getting ships into Saigon to load the prisoners. About September 1944 the Australian prisoners were taken back up the Mekong River into the River Road Camp and met up with a lot of our old friends in Varley Force, which had also tried to get out of Saigon after us and had been brought on down to Singapore.

During our stay we were employed on various duties, in the main light ones, but the rations were poor and limited, but we were able to pick up a bit extra when working on the wharves in Singapore loading and unloading the Japanese ships.

Eventually on 16 th December, we were moved out of River Valley Road camp and herded onto a passenger ship called the ‘Awa Maru’, and at first the moderness of the ship led us to believe that we might obtain better travelling conditions than we had experienced up to date. In the event however, we were all 600 of us crowded into a small triple-tiered hold with only about four feet of headroom between tiers. Each tier had to accommodate 200 prisoners. The ‘Awa Maru’ lay in Singapore Harbour for about 10 days while a convoy of 4 oil tankers and two merchant ships was assembled. A number of Japanese civilians – men, women and children – also travelled in the ship in much the same conditions as we did, except that they were less crowded. The better class accommodation available on the ship was unoccupied. The prisoners had a torrid time below decks in the tropical temperatures and humidity with no ventilation, and after approaches to the Japanese they relented after several days and allowed us on deck in relays, but at night we were all pushed down below.

The convoy sailed on the 26th December, 1944, much to our relief. Generally we hugged the coast line of the various places we passed through during the day in the shallower water, and often sheltered in small harbours at night, but the trip was uneventful except for two separate torpedo attack alarms. As the convoy proceeded north the climate became more temperate and conditions below decks were more tolerable. With our limited room it was sufficient for each man to sit up with legs drawn up under the chin and to huddle together, we were best able to combat the cold weather.

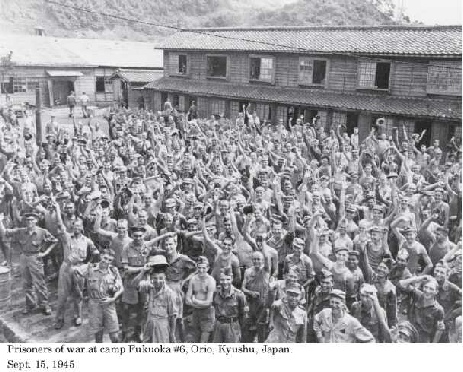

On the 15th January we reached Moji, one of the few convoys to reach Japan unscathed in this

period, a fact attributable to the preoccupation of the U.S.A. in the Philippines. We landed in a heavy

snow storm (what a contrast after 3 years in the tropics), and all prisoners were assembled in the

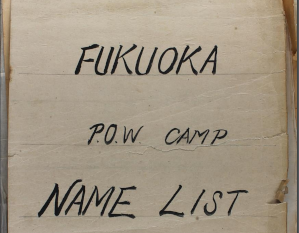

wharf buildings and separated into groups for allocation to various coal mines in the Fukuoka area. The writer with Bernie Cantwell and Mac Reid were the 2/19 Bn members who found themselves

despatched to Fukuoka 21 camp, and the remaining 2/19 chaps were assigned to various other

prison camps in the Fukuoka area.

The writer with Bernie Cantwell and Mac Reid were the 2/19 Bn members who found themselves

despatched to Fukuoka 21 camp, and the remaining 2/19 chaps were assigned to various other

prison camps in the Fukuoka area.

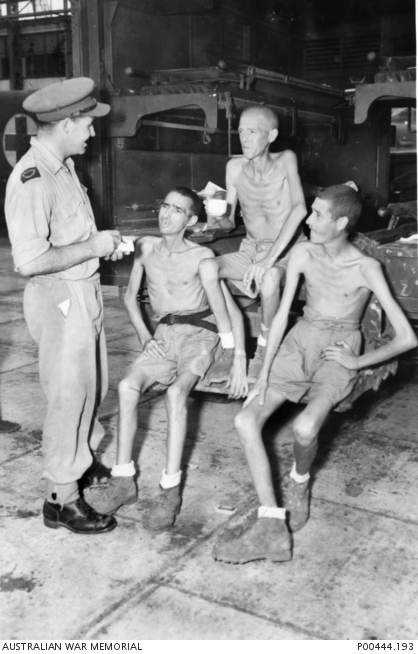

In Fukuoka 21 Camp there were approximately 100 Australian Prisoners, including Navy, Air Force and some 6 th Div. A.I.F., who had been taken prisoner at Java. We were all soon to experience the effects upon the human body of poor diet, extreme cold weather and long hours of working underground in the coal mines.

At Fukuoka 21 Camp we were soon allocated various duties at the coal mines – one half of the personnel on day shift and the remainder on night shift, with a change of shifts each ten days. On each 10-day changeover, prisoners were remunerated for work by a ‘presento’ of 10 cigarettes, plus one small onion for those workers who had worked hard for the Japanese Emperor. (There were few, if any, Australians who ever participated in the handout of onions).

Conditions in the coal mines were poor – it had been closed for many years – roof timbers were rotting and there were frequent cave-ins. Surprisingly enough, most of the serious cave-ins occurred during the silent hours when there was no-one working in the mines, but working in waist-deep water caused great discomfort.

Red Cross parcels arrived at Fukuoka 21 Camp from time to time, the boxes were opened by the guards and contents locked in the storeroom for the exclusive use of the Japanese. Little or no Red Cross supplies ever found their way to the prisoners Medical supplies were held at the camp in locked cases, with instructions that a record be maintained of all materials used. The Japanese Medical Officer (3 rd class private) decided that it would be easier not to use any medical supplies, and therefore he would not have to keep any records. Consequently prisoners were not given these medical aids.

Two additional groups of prisoners arrived at the camp from the Philippines. The first group comprised U.S.A. officers. Very few of these arrived alive at Fukuoka, because many had gone beserk during the trip from the Philippines, following their pilfering of sugar from the cargo and the lack of water aggravated their extreme thirst. We were told that the Japanese guards had to shoot the prisoners to restore order. The second group of U.S. prisoners arrived soon after the first lot and commenced working in the coal mines, although in different sections from the Australians.

Japanese civilians were working in the coal mines and had control of the prisoners. During the time the prisoners were underground the civilians had full responsibility, and we could always tell the state of how the war was progressing by their attitude to us. Working hours became longer as the air raids increased, and blackouts were enforced which necessitated the stoppage of the mine machinery. As the Allies increased air raids, more and more time was spent underground – day and night shifts overlapped each other – lamp batteries became exhausted, and prisoners had to grope their way from the working shaft approximately one mile underground up to the mine head.There were approximately 1400 steps to get out of the mine. On reaching the mine head, Japanese guards again assumed responsibility and forced prisoners to run all the way to the Camp in between the raids, and spend the next few hours in the air raid shelters until it was time to go back into the coal mines.

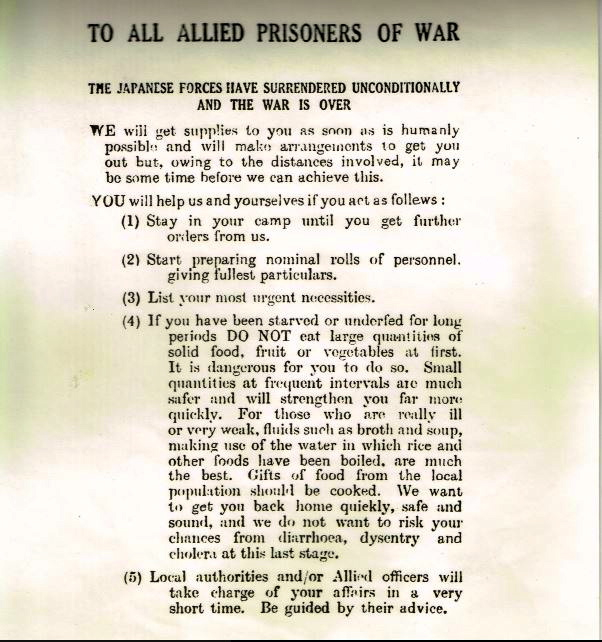

There were rumours that the war was nearing the end when work stopped one day and rations were cut to half. All prisoners were firmly convinced at this stage that there was no possibility of them surviving another winter in the coal mines. All the workers were completely exhausted and they had no reserves to get through another cold winter. Mac Reid from the 2/19 Bn. was 41⁄2 stone (a little under 27 kilos) and still working on the coal faces. What saved the prisoners was the dropping of the atomic bomb, because the Japanese were preparing for an invasion, but had no answer to the terrific damage inflicted by these bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Soon after the war finished American planes from Guam dropped food to the prisoners in the Fukuoka area, and we received messages from the American Air Force that the coal mines were the next objective for bombing by the Allies had the war not been finished. Prisoners were moved to Nagasaki, and thence by aircraft carrier to the Philippines. After medical attention etc, we were taken to Australia by British aircraft carriers the ‘Formidable’ and the ‘Speaker’.

Anderson Andrew Walter John ,VX19224,Pte,2/2 Pioneer,

Anderson Andrew Walter John ,VX19224,Pte,2/2 Pioneer,LEST WE FORGET

Original Australian Roster Download

Thank a teacher.... If you are reading it in English, thank a Veteran!